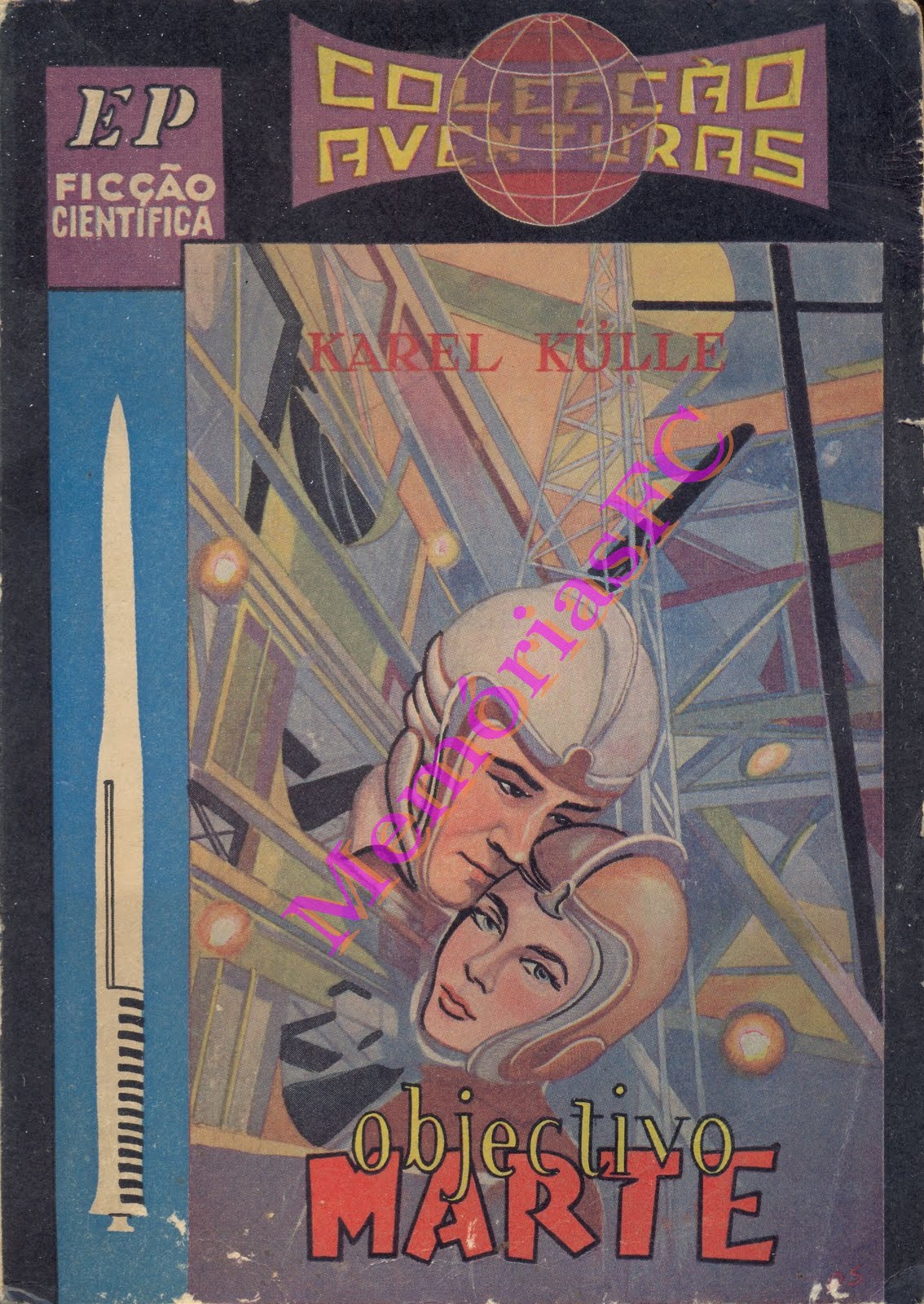

A publicação desta semana de 23 a 28 de Novembro de 2015 é uma obra de ficção científica nacional contemporânea da fase final da "idade de ouro" do género no mundo anglo-saxónico e de transição para a ficção científica de Nova Vaga dos anos '60 e '70 (a "idade de ouro" deste género é considerada como tendo sido entre 1938, fim da "era da pulp" na fc publicada em imprensa do género, e 1946, os anos '50 sendo considerados "só" época de transição para muitos fãs e críticos do género, embora alguns como Robert Silverberg, autor do género, co-organizador com Lima Rodrigues de uma versão incluíndo textos de autores Portugueses da colectânea do género Terrestres e Estranhos publicada pela Galeria Panorama em 1968 e autor hoje "em contrato" com a Antagonista Editora para publicação em Portugal, achasse que os anos '50 fossem uma continuidade da "idade de ouro" e até os anos mais "de ouro" e típicos da era). Publicado em 1959 pela colecção EP - Ficção Científica da Editorial Popular de F. Bento & Correia Lda. de Lisboa, este foi o segundo relativo sucesso do autor Karel Külle. Mas quem era este autor de nome vagamente nórdico-centro-europeu (Karel é o equivalente de Carlos checo e holandês, Külle surgindo, normalmente sem os pontos conhecidos colectivamente em Alemão como umlaut, em Sueco ou Checo, existindo um apelido similar, com umlaut sobre o u, Ülle, na Estónia)? Não um qualquer autor estrangeiro, mas, por via de mais um caso da prática (que sem discutirmos já vimos algumas vezes até agora) da pseudo-tradução (em que um autor Português, para evitar, entre outras coisas, censura, que durante o Estado Novo tendia a "chatear" mais autores nacionais que estrangeiros, ou para evitar o "estigma" da escrita em género ditos "menores" como policial, fantástico ou ficção científica ao "bom-nome", finge estar a traduzir um autor estrangeiro, o verdadeiro autor tendendo a surgir indicado como tradutor mas por vezes para maior despiste, surgindo o nome de um tradutor profissional da mesma editora), de um autor Portuguesíssimo. Neste caso (como frequente quando um nome que não surge em muitas traduções surge numa mão cheia de obras como tradutor) o tradutor é o verdadeiro nome por detrás de Karel Külle: Carlos Filomeno dos Anjos de Sousa Sardinha, que em 1958 havia "traduzido" o policial A Grande Ameaça sob o pseudónimo de Russel Randall (para a Agência Portuguesa de Revistas), e antes de "criar" Karel Külle já havia produzido pseudo-tradução (mas em ficção romântica) também em 1959 como Pierre de Juvissy (nome que terá sido composto da conjugação de largos em Juvisy-sur-Orge, alguns quilómetros a sul de Paris, com nomes de Pierres, o que junto com a inspiração nórdico-balto-eslava de Karel Külle poderão indicar que estamos ante um autor viajado ou pelo menos culto quanto ao exterior) no romance Se todos os anjos voassem... (para a editora Popular), e ainda antes de Objectivo Marte escreveu (com um pouco menos de vendas e visibilidade, visibilidade no nível de obra 'pulp popular' entenda-se) Bula Matari. 1959, o seu ano mais produtivo como romancista (ou "pseudo-tradutor") acabou com o último romance de Külle, Tigres no Céu.

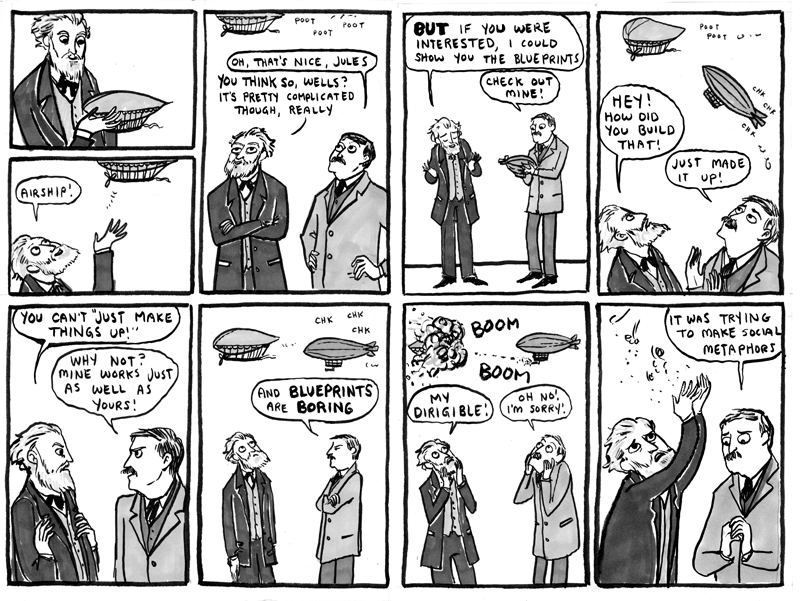

Carlos Sardinha foi um erudito e intelectual de respeito, que em 1967 dirigiria a revista dedicada a S. Tomé e Príncipe chamada Equador. Sardinha tinha um grande interesse em questões e problemas coloniais (também o demonstra o título dado a Bula Matari; era o nome que os nativos Congoleses deram ao jornalista Henry Morton Stanley quando lá andou em busca do missionário e explorador David Livingston, que cumprimentou com o famoso "Dr. Livingston, suponho?", significando "Parte Pedras" devido a ele frequentemente auxiliar os guias nativos a partir pedras pelo caminho, havendo discussão se a alcunha era dada como louvar ou ironia ante um branco que se "rebaixava" a fazer trabalho para trabalhadores negros). Um leve (e nada panfletário) elemento de crítica social e (no caso da sua ficção científica) analogia e alegoria da situação colonial portuguesa e geral surgem na obra ficcional "traduzida" pelo autor. Sardinha foi desde a sua primeira obra, ainda no policial, relativamente bem vendido para um autor das edições baratas "de género" que eram a "literatura de cordel" do Portugal de meados do século XX, e um caso ainda mais curioso tendo em conta que um erudito de pouca visibilidade e trabalhador de editoras (primeiro da Agência Portuguesa de Revistas e depois de outras) que nem sequer era o nome que surgia na capa dos livros que ele próprio escrevia conseguia ser lido e apreciado por um certo número de leitores jovens e de classe média e média-baixa numa altura de alfabetização ainda baixa em Portugal e em que os livros ainda eram um luxo (embora este tipo de edições fossem das mais acessíveis. Assim, Carlos Sardinha tornou-se no nosso país um vagamente conhecido autor de policial e de ficção científica sem as pessoas repararem no seu nome (disfarçado de "mero" tradutor). E podemos perguntar-nos quantos fãs deste género ainda marginal em Portugal não o terão lido na juventude sem saberem ler um autor nacional, e terão sido influenciado para criar no género vagamente pulp e aventureiro de ficção científica em que ele criou literatura.O que faz de Objectivo Marte um marco na literatura de ficção científica em Portugal é que é a primeira vez na literatura nacional do género vai para o espaço voluntariamente em em máquinas mais ou menos realistas, não envolvendo invenções feitas na terra, nem "armas do juízo final" ou "raios da morte" (que até no cinema português já haviam aparecido em 1941), intervenção dos ETs em Portugal (como na peça radiofónica A Invasão dos Marcianos de Matos Maia de 1958), ou viagens ao espaço por acidente (do tipo balão setecentista voado para o espaço exterior por acidente de História Autêntica do Planeta Marte do nosso já conhecido Nunes da Mata em 1921) ou viagens autênticas mas em máquinas aerostáticas primitivas que nunca de facto poderiam voar tão longe da terra (em poemas herói-cómicos dos séculos XVIII e XIX como O Foguetário de Pedro de Azevedo Tojal, A Maquina Aerostatica de João Robert da Fond, e Viagens no Sytema Planetário de Patrocínio da Costa), mas também pela forma como se faz analogia (como em todos os romances do género de "Karel Külle") com a colonização africana de Portugal, que surge aqui por alegoria analisada intelectualmente de uma forma tão crítica como não propriamente apelando a descolonização. O extraterrestres, que surgem como antropomórficos e de civilizações algo utópicas (nas obras de Külle como na de Juvissy) são assim os Africanos, com os exploradores do espaço sendo os colonizadores Portugueses. O estilo de Carlos Sardinha, além de pulp e aventureiro como já dito, é também não demasiado preciso na parte técnica e científica das máquinas, como a maioria dos autores do género (com excepções como Júlio Verne ou o também cientista Isaac Azimov). Enquanto Nunes da Mata (como Verne) é um entusiasta da ciência e da matemática e isso é claro no cuidado apresentado no realismo da sua poesia narrativa ou prosa (mesmo quando aparentemente fantástica como na História Autêntica do Planeta Marte), enquanto Sardinha (como H. G. Wells) cria só o básico para sustentar as invenções ou eventos que mostra e está principalmente interessado nestes enredos pela alegoria ou comentário sociais que podem dar.

Cartoon contrastando os modos de fc de Verne e Wells (do sítio Hark! A Vagrant)

O enredo em si, envolve a partida de um vaivém chamado «Argonauta I», numa partida, com público assistindo e tudo, descrita de uma forma bastante realista para quem vê hoje as imagens da partida dos foguetões soviéticos ou americanos («Na base do foguetão, as chamas estralejavam. O «Argonauta I» moveu-se lentamente, como se quisesse desafiar a emoção dos assistentes. Sùbitamente [ainda influência da grafia 1911-1942 do Português], como que tomado de estranho poder, investiu contra o céu, transformando-se numa remota safira no firmamento.»). Além da «mais fantástica aventura de todos os tempos: A conquista do Sistema Solar!» (como diz o livro logo a seguir da descrição da partida), existe a dinâmica romântica criada por um casal formado por dois dos astronautas do «Argonauta I». Sem mais revelações de enredo, livro recomendado, infelizmente raro que ainda se consegue encontrar à venda online.The post of this week from November 23 to 28 2015 is a work of contemporary Portuguese science fiction from the later phase of the genre's "golden age" in the anglo-saxonic world and of transition to the New Wage science fiction from the '60s and '70s (the "golden age" of this genre is considered as having been between 1938, end of the "pulp era" on scifi published in genre press, and 1946, the '50s being considered "just" transition time for many fans and reviewers of the genre, although some like Robert Silverberg, author on the genre, co-organiser with Lima Rodrigues of a version including texts from Portuguese authors of the collection from the genre Earthmen and Strangers/Terrestres e Estranhos published by the Galeria Panorama publishr in 1968 and author today "under contract" with the Antagonista Editora for publication in Portugal, found that the '50s were a continuity of the "golden age" and even the more "golden" and typical years of the era). Published in 1959 by the EP - Ficção Científica collection from Lisbon's Editorial Popular de F. Bento & Correia Lda. publisher, this was the second relative success of the author Karel Külle. But who was this author of name vaguely nordic-central-european (Karel is the Czech and Dutch equivalent to Charles, Külle comming up normally without the dots known collectively in German as umlaut, in Swedish or Czech, existing a similar surname, with umlaut on the u, Ülle, in Estonia)? Not any foreign author, but, via one more case of the practice (that we saw some times till now) of the pseudo-translation (in which a Portuguese author, to avoid, among other things, censorship that during the Portuguese New State tended to "annoy" more Portuguese than foreign authors, or to avoid the "stigma" of the writing in genres said to be "minors" like the detective-mystery/crime story, fantasy or science fiction on one's "good name", pretends to be translating a foreign author, the true author tending to come-up indicated as translator but sometimes for greater muslead, coming-up the name of a professional translator from the same publisher), of a most Portuguese author. In this case (as frequent when a name that doesn't appear in many translations comes-up as such on a handful of books as translator) the translator is the true name behind Karel Külle: Carlos Filomeno dos Anjos de Sousa Sardinha, who in 1958 had "translated" the detective-mystery/crime story A Grande Ameaça ("The Great Threat") under the pen-name of Russel Randall (for the Agência Portuguesa de Revistas/"Portuguese Agency of Magazines"), and before "creating Karel Külle he had already produced pseudo-translation (within romantic fiction) also in 1959 as Pierre de Juvissy (name that would been composited out of plazas at Juvisy-sur-Orge, some kilometers sout of Paris, with the names of Pierres, what together with the nordic-balto-slavic of Karel Külle could indicate that we are before a travelled author or at least cultivated about the abroad) in the novel Se todos os anjos voassem... ("If all the angels did fly..." for the Portuguese Popular publisher), and still before Objectivo Marte/"Objective Mars" wrote (with a little less sales and visibility, visibility on the level of 'pulp popular' literature to be understood) Bula Matari. 1959, his most productive year as novelist (or "pseudo-translator") ended with Külle's last novel, Tigres no Céu/"Tigers in the Sky".

Carlos Sardinha was a respectable scholar and intellectual, that in 1967 directed the magazine dedicted to Sao Tomeh and Principe called Equador ("Equator").Sardinha had a great interest on colonial questions and problems (it also demonstrates it the title given to Bula Matari; it was a name that the Congolese natives gave to the journalist Henry Morton Stanley when he went along over there in search of the missionary and explorer David Livingston, whom he greeted with the famous "Dr. Livingston, I presume?", meaning "Stone Breaker" due to him frequently aiding the native guides to break stones along the way, there being discussion if the nickname as given as appraisal or irony before a white that "lowered" himself to do work for black workers). A light (and not at all panfletary) element of social criticism and (in the case of his science fiction) analogy and allegory of the Portuguese colonial situation in general come-up in the fictional work "translated" by the author. Sardinha was since his first work, still in the detective-mystery/crime story, relatively well sold for an author of cheap "genre" editions which were the "chapbook literature" from the Portugal of the mid-20th century, and a care even more curious having in mind that a scholar of little visibility (first from the Portuguese Agency of Magazines and afterwards from others) that not even was the name that came-up on the cover of the books that he himself wrote could be read and appreciated by a certain number of young and middle and lower-middle class at a time-point of literacy still low in Portugal and in which books still were luxuries (although this type of editions were among the most accessible). So, Carlos Sardinha became in his country a vaguely known detective-mystery/crime and science fiction author without people noticing on his name (disguised as "mere" translator) and we can ask ourselves how many fans of this genre still marginal in Portugal would not have read it in their youth without knowing to be reading a Portuguese author and would have been influence to create on the vaguely pulp and adventurous genre of science fiction in which he created literature.What makes Objective Mars a stepping stone in the science fiction literature in Portugal is that it is the first time in the Portuguese literature of the genre goes to space voluntarily and in machines more or less realistic, not involving inventions made on earth nor"doomsday machines" or death rays" (that even on the Portuguese cinema already had appeared in 1941), intervention of the ETs in Portugal (as in the War of the World radioplay A Invasão dos Marcianos/"The Invasion of the Martians by Matos Maia from 1958), or travels into space by accident (from the type of the seventeen-hundredth baloon flown to outer space by accident from História Autêntica do Planeta Marte/"Authentic History of the Planet Mars" by our already acquainted Nunes da Matta in 1921) or authentic travels but in primitive aerostatic machine that never indeed could fly so far from the ground (in mock-heroic poems from the 18th and 19th century like O Foguetário/"The Firewarking" by Pedro de Azevedo Tojal, A Maquina Aerostatica/"The Aerostatic Engin" by Joao Robert da Fond, and Viagens no Sytema Planetário/"Travels on the Planetary System" by Patrocinio da Costa), but also fhr way as it is done analogy (as in all the novels in the genre by "Karel Külle") with Portugal's african colonisation that comes up here by allegory analysed intellectually in way as critical as not properly appealing to decolonisation. The extraterrestrials, that come-up as anthropomorphic and from somewhat utopian civilisations (in Külle'd works as in Juvissy's) are thus the africans, with the space explorers being the Portuguese colonisers. Carlos Sardinha's style, besides pulp and adventurous as already said, is also not too much precise on the technical and scientifical part of the machines, as most of the genre's authors (with exceptions like Jules Verne or the also scientist Isaac Azimov). While Nunes da Mata (as Verne) is a science and mathematics enthusiast and that is clear in the care presented on the realism of his narrative poetry or prose (even when apparently fantastical as in Authentic History of the Planet Mars), while Sardinha (like H. G. Wells) creates just the basic for supporting the inventions or events that he shows and is mainly interested in these plots for the allegory or social comment that they can give out.

Cartoon contrasting the scifi moves of Verne and Wells (from the site Hark! A Vagrant)

The plot in itself involves the departure of a shuttle called «Argonaut I», on a departure, with the audience watching and all, described in a quite realistic way for who sees today the images of the departure of the Soviet or American shuttles («On the shuttle's base, the flames crackled out. The «Argonaut I» moved itself slowly, as if it wanted to challenge the emotion of the watchers. Sudenli [archaic for "Suddenly" to parallel the Subitamente written Súbitamente still under influence of the 1911-1942 spelling of the original Portuguese], as if taken-over by strange power it vested against the sky, transforming itself into a remote saphire on the firmament.»). Besides the «most fantastical adventure from all times: The conquest of the Solar System!» (as says the book right-after following the departure's description), it exists the romantic dynamic created by a couple formed by two «Argonaut I» astronauts. Without further spoilers, recommended book, unfortunately rare to find itself for sale online.